In this article, we’re going to examine another antipattern around story point estimation. Last time we discussed the fallout of using story points as targets. Now, we caution you against using story points to compare teams. It’s a common enough trap, but we must hold ourselves back. By the end of this article, you’ll know why such comparison is a meaningless exercise.

What’s the comparison about?

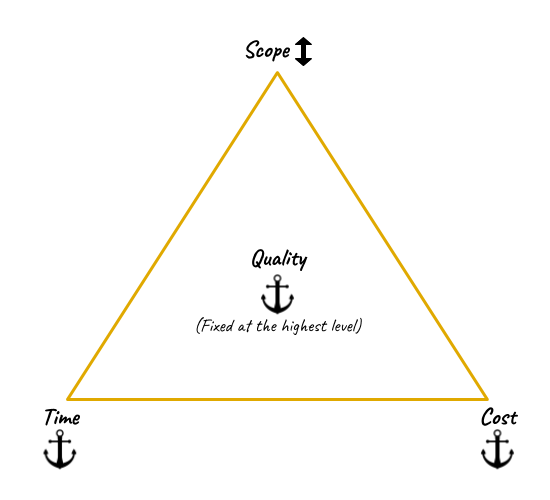

To put it simply, using story points to compare team has accusatory implications. “Hey this other team is doing more points per iteration than your team, so that makes them better.” So Team A could be doing 20 points and Team B could be completing 12 points, and because Team A’s velocity is greater, it’s the better team. When put like that, we will naturally witness Team B desperately try to outdo Team A, or at least match its velocity. End result: Pressure builds up, the environment can get ugly, team members may resort to workarounds to meet the numbers, and little thought will go toward what should really be in the focus – the quality of the software that’s going into production.

Here’s why such comparison is meaningless

Despite the exercise having no real meaning or value, we still find many teams engaging in it during story point estimation. We reiterate that such thinking, i.e., comparing teams on the basis of completed points, is totally flawed, and here are our reasons for taking this stance:

Every team is unique

Each team has its own distinct personality and comes with diverse skill sets and levels of experience. No two teams are alike in their inter-personal as well as working relationships – how well they gel together, how effectively can they collaborate, etc. Then there are more factors like do they have any dependencies, what’s the environment in which they work, and so on.

All these factors contribute to the uniqueness of each team. Hence it is completely unfair and impractical to compare velocities because it would be impossible to create two teams that have the exact same skills and the same personalities and do the same kind of work in the same environment. Velocity is a reflection of many things happening within a team – As we saw above, each team comes with its unique composition, skills, experience, and dynamics. All of these have a bearing on how long that team will take to complete a story and how much they can pack into one iteration. This output will vary across teams and there is no ground for comparison.

The understanding of a point is not common across teams – The basis of comparison is itself skewed. As we saw earlier, comparison takes the form of: Team A completed 20 story points but Team B could complete only 12 in the same duration. What we fail to realize is that each team’s understanding of what makes up 1 story point is limited to that team and it will differ across teams. This understanding of how big is the backlog is not standard; it’s relative to each team. What Team A considers to be 1 point can be very different from the perspective that Team B takes. Note that 1 point is just a numeric representation for a “small” story. And 4 points would be just a numeric representation of a large story. But the buckets of what is a small story is only relevant and meaningful within the team. How then can we compare their performance and efficiency on the basis of the number of points completed?

A standard definition of 1 point doesn’t work

To counter the above problem, some folks go a step further and say everyone must agree upon a standard definition of 1 point, so everyone can align the sizes for stories. While this sounds reasonable this is very difficult to achieve in practice. The cost of the bureaucracy required to ensure this especially on a large program OR for the entire organisation is hardly worth the ability to compare teams’ velocities.

The nature of each team’s work can be different

So let’s say there are two teams in the organization that are fundamentally doing very different kinds of work. One is building some API’s and the other is building a mobile app. It’s a no-brainer that the tech landscape and the kind of complexities faced by each team are extremely different. In such a scenario, comparing how fast they are completing their points is fundamentally meaningless!

Similar work cannot be compared either

Let’s look at cases where teams could be involved in similar work, such as both teams are building on top of a common API. One is building an Android app and the other an iOS app. It may seem like they are doing similar work, but even then, it’s not so straightforward that we can begin comparing their velocities. That’s because contributing factors such as environment, skills, etc. continue to remain different.

Let’s look at a typical development scenario where two teams are working on the same backlog – one is onshore, the other is offshore. On one hand, we can safely assume that that the onsite time will go faster because the Product Owners are sitting next to them, providing real quick answers or feedback. On the other hand, this same situation may work to their detriment. The team members may find themselves getting distracted because the client stakeholders are right there. The offshore team doesn’t face that pressure and may be able to focus more effectively and actually end up with a higher velocity. But, truly, can we conclude that they are really more efficient? We cannot, because the comparison itself has no real meaning.

How to avoid the antipattern of comparing teams using story points

The above reasons illustrate the futility of such a comparison. That’s why we strongly recommend against comparing teams. It’s not a valuable exercise to say one team is better than the other by itself. But if at all you have to compare or you want to compare, then track the trends of each team, such as the level of predictability, frequency of releases, or the business impact they create.

Predictability

Have the teams set up short-term goals or iteration-level targets and then track how often each team is able to meet its targets. The targets can vary across iterations, depending on factors like yesterday’s weather. But if a team says on a Monday that in the next two-week-long iteration, they will complete 10 points, then how often do they actually achieve that completion? Or how close do they get to it every time? This level of predictability can be compared, if at all one really has to.

Frequency of releases

The more frequently the team is putting software into production and into the hands of real users, the more value they are creating. So you can compare how frequently each team is able to create such value.

Business Impact

Mature XP teams don’t even bother with intermediate output; they are more concerned with the outcome, i.e., the business impact the team is able to create. The way you do that is to have the team sign up for key OKRs. These could be key business results they want to achieve such as improving customer conversion or reducing churn in customers. That’s the business objective they work toward. And whether they deliver software to achieve that or do something else – that’s entirely up to the team.

However, this extreme practice of only measuring business outcomes may not be feasible in every software development scenario, but the takeaway from that is to not just measure output, but measure on these more meaningful aspects.

However, it’s again important to bear in mind that you shouldn’t be comparing on parameters such as the revenue each team is able to generate. That’s because each team functions in a different context and could have distinct strategies. One team’s focus could be revenue generation, another team could be driving consumer engagement–which again eliminates any common ground for comparison. So, even if we’re comparing on the parameter of business impact, the OKRs are not to be compared. How far each team is able to achieve its OKRs is more important.

By now, you have got a chance to understand the various reasons to avoid comparing teams in itself. Comparing teams on velocity and the points they’ve delivered has absolutely no meaning. If at all you have to compare and want to compare, then you can certainly find ways to make the comparison more relevant and meaningful. The outcome of such comparisons has more value.